I couldn’t find a picture that related to what I was writing about (I always try to do that), in this case the Spanish subjunctive, so here’s a picture of my idea for an anti-gravity device based on a cat with some buttered toast on its head – what do you think?

I couldn’t find a picture that related to what I was writing about (I always try to do that), in this case the Spanish subjunctive, so here’s a picture of my idea for an anti-gravity device based on a cat with some buttered toast on its head – what do you think?

The subjunctive in Spanish is one of two other moods besides the ‘normal’ Spanish mood (and it is a mood, not a tense) that you’re used to, which is called the indicative mood (in short, it’s used to state things the speaker believes to be facts as opposed to opinions or hypotheticals), and the other one is the imperative mood which is solely used to give commands. The Spanish subjunctive is used with impersonal expressions and expressions of emotion, opinion, doubt, disagreement, denial or volition – essentially, it’s used for anything uncertain or emotional. The indicative is used for expressing things that are objective, truthful, unemotional, and not in doubt. I should also note that the subjunctive, though essential to becoming fluent in Spanish (or even moving beyond the beginner’s level), is note often used and shouldn’t be bothered with until you’re on the tail end of learning beginner’s Spanish (that is you’re just finishing up with A2 on the CEFR scale). If you’re not sure, or would like to learn more about which verb tenses/moods you should focus on depending on your level, please see my article entitled, What Spanish Verb Tenses You Should Learn First, and Why They’re So Important.

If you wanted to say that the cat is on top the refrigerator, you would just use the regular indicative: “El gato está encima de la nevera”, however, if you wanted to say that the cat would prefer that you not put him on top of the refrigerator, you would use the subjunctive and say: “El gato desea que no lo pongas encima de la nevera”, where “pongas” is the present subjunctive form of “poner“. You’ll notice that the first verb is in the normal indicative mood, whereas it’s the second verb that’s in the subjunctive and that’s how it always is, which brings me to…

Requirements

There are three requirements that usually must be met for the Spanish subjunctive to be needed. These are not always necessary, they’re more like “characteristics that are present 95% of the time”, but as this is an introductory article for people who have never delved into the subjunctive before, that’s good enough for our purposes. They are:

1. Two different subjects

2. A relative pronoun (“que”, “como”, “cual”, “donde”, or “quien”)

3. Two different verbs – the first will always be in the indicative and the second will always be in the subjunctive. The first verb will signal that the second verb needs to be in the subjunctive by the very nature of that first verb and the context it’s used in (it expresses emotion, doubt, etc.).

There must also be two Clauses, though this is an automatic consequence of requiring 2 subjects so it doesn’t get its own rule.

W.E.I.R.D.O.

This is a brilliant little system for figuring out when you need to use the subjunctive in Spanish (I don’t know who originally invented it, but it wasn’t me). Like I said above in the third requirement: the first verb, which is almost always in the indicative, will tell you if the second verb needs to be in the subjunctive or not. As you already know, you’re looking for verbs that express emotion, uncertainty, desire, etc. Well, there’s a nifty little acronym you can use to help you remember all of these with ease. All you have to do is remember to look for W.E.I.R.D.O. verbs:

Wishes

Emotions

Impersonal Expressions

Recommendations

Doubt/Denial

Ojalá

Wishes: This includes all wishes, wants, demands, desires, orders, expectations, and preferences. Examples include things like “Espero que él me llame” which means “I hope that he calls me”, or “Todos quieren que vengas” which means “Everyone wants you to come.”

(note: all subjunctive verbs in these example sentences are bolded)

Verbs in this category that commonly indicate the need for the subjunctive to follow include mandar (to order), insistir (to insist), necesitar (to need), preferir (to prefer), querer (to want), desear (to wish or desire), pedir (to request), etc.

Emotions: Any time someone is expressing the fact that they’re annoyed, angry, happy, sad, scared, surprised, etc. you will almost always see the subjunctive used due to this being considered an expression of emotion. Examples include the above example I gave with the angry cat, or something like: “A Benny le molesta que la gente coma animales aunque ellos son muy sabrosos.” which means “It annoys Benny that people eat animals even though they are very tasty.”

Verbs that commonly fall into this category are alegrarse (to be glad), gustar (to like), encantar (to love in the sense of really liking something), lamentar (to regret), enojar (to be angry), sorprender (to surprise), temer (to fear), quejarse (to complain), and molestar (to annoy).

Impersonal expressions: These express someone’s opinion or judgment on something and are subjective in nature. Examples include things like “Es extraño que el gato esté volando” which means “It’s strange that the cat is flying”, or “Es bueno que hayas decidido darme todo tu dinero” which means “It’s good that you’ve decided to give me all your money.”

Common expressions in this category are things like “es agradable” (it’s nice), “es necesario” (it’s necessary), “es raro” (it’s rare), “no es cierto” (it’s not certain), “es increíble” (it’s incredible), “es malo” (it’s bad), etc.

Recommendations: Whenever someone is recommended, suggested, or told to do something, this falls into the recommendation category. Things like: “Mi doctor recomienda que no beba tanto vodka” which means “My doctor recommends that I not drink so much vodka”, or “Ellos sugieren que no juegues en el tráfico” which means “They suggest that you not play in traffic.”

Verbs commonly seen in this category include aconsejar (to advise), sugerir (to suggest), recomendar (to recommend), rogar (to beg), ordenar (to order), and proponer (to suggest or propose).

Doubt/Denial: Whenever someone wants to express doubt or denial, they use the subjunctive. Examples include things like: “Dudo que tengas un burro morado” which means “I doubt that you have a purple donkey” or perhaps “No creo que él diga la verdad sobre su coleccíon de arbolitos” which means “I don’t believe he’s telling the truth about his shrubbery collection.”

Verbs commonly used to express doubt include dudar (to doubt), creer (to believe), pensar (to think), negar (to deny), “no estar seguro” (to not be sure), suponer (to assume or suppose), etc.

Ojalá: “Ojalá” is an interesting word you’ll hear very frequently in Spanish, particularly Latin American Spanish. It is one of several Spanish words that has Arabic origins. It comes from the Old Spanish oxalá, which comes from the Arabic لو شاء الله (law sha’a Allah) and means something like “if God wills it”. So ojalá means “If only…” or “I hope to God…” or, basically, “I really hope…”, so you can see why it requires the subjunctive because it’s expressing a desire in a special sort of way. Examples include things like: “Ojalá que lleguen pronto las mujeres desnudas”, meaning “I hope to God the naked women arrive soon”, or “Ojalá que no me dispare en el culo” which means “I really hope he doesn’t shoot me in the ass”.

Bonus: Hypotheticals

To describe hypothetical situations Spanish speakers frequently employ the subjunctive, often in conjunction with the expression, “como si”, e.g. “como si fuera”, “como si estuviera”, etc. This makes perfect sense as the subjunctive is used to describe, generally, something that doesn’t exist or isn’t the case but maybe could be. Here are some examples from real-life contexts:

Deberían tratarla como si fuera sagrada.

“They should treat it as if it were sacred.”

Me gritaba como si fuera niño.

“She’s was yelling at me as if I were a child.”

Siento como si estuviera dormida aquí.

“I feel as if I were asleep here.”

Estás mirándome como si estuviera loco.

“You’re looking at me as if I were crazy.”

Searching Reverso Context for “como si” yields tons of examples of this in practice, definitely have a look for more examples of this phenomenon in the wild.

Further Reading and Additional Resources

Reading an explanation of grammar concepts like the Spanish subjunctive won’t make it so that you can use such grammar concepts, it’s just the first step on that journey: you have to apply what you’ve learned, you have to practice. The best way to do this, of course, is by communicating with actual native speakers, using the grammar you’ve just learned, and having them help and correct you. An excellent way to go about this is with an online course called GoSpanish that I recommend: it’s much cheaper than a one-on-one tutor but you’re still working with a native speaker, class size is 3-5 students each, and you get unlimited (yes, a dozen a day if you like) classes starting at just $39 per month. Check out my review here of GoSpanish.

Definitely check out this post’s parent category, Basic Spanish Grammar Rules: Lessons & Explanations, for more similar articles such as:

- Why learning verb conjugations is important and which ones you should learn first, or

- A brief guide to regional variation of the forms of address in Spanish (usted, tú, vos, etc.) or even…

- A list of YouTube channels that teach Spanish (much of it consisting of grammar lessons)

SpanishDict also did an excellent video on the Spanish subjunctive where they go through the W.E.I.R.D.O system if you’d like to have a look at that, it’s 2 parts and about 12 minutes long in total:

Part 1

Part 2

I hope that was interesting, let me know what you think in the comments (and would like me to write about in the future).

Cheers,

Andrew

I learned to speak conversational Spanish in six months using TV shows, movies, and even comics: I then wrote a book on how you can, too

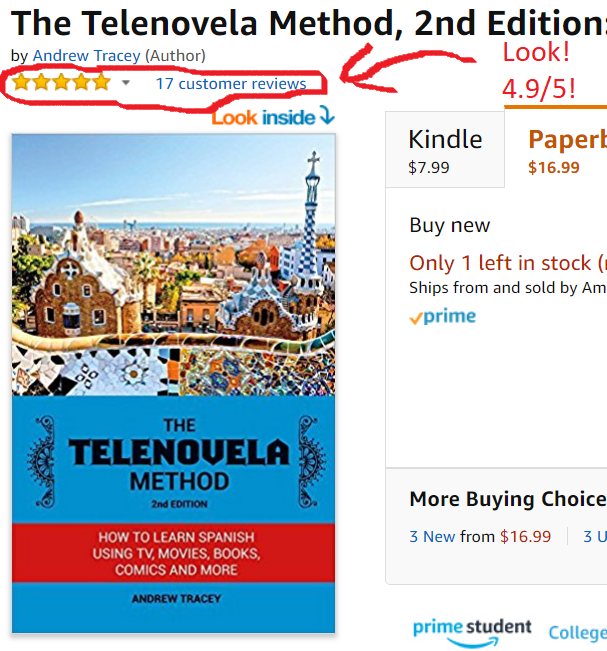

I have a whole method and a book I wrote about it called The Telenovela Method where I teach you how to learn Spanish from popular media like TV shows, movies, music, books, etc. that you can all find online for free. It was the #1 new release in the Spanish Language Instruction section on Amazon for nearly a month after it came out and currently has 17 reviews there with a 4.9/5 stars average. It's available for $7.99-$9.99 for the e-book version depending on who you buy it from (Kindle version on Amazon is now $7.99) and $16.99 for the paperback (occasionally a bit cheaper, again, depending on who you buy it from).

It's currently available in both e-book and paperback from:

Cheers,

Andrew