This is the 6th in a series of posts I’m doing where I help you learn Spanish from music videos and show you how I do it myself (that way you don’t have to wait for me to dissect a Spanish music video, you can go out and start doing it yourself with whatever songs you want and using it to teach yourself Spanish). I’ve done five other similar posts prior to this: the last one on Juanes’ ‘Yerbatero’, the fourth one on Shakira’s ‘Te Aviso, Te Anuncio’, the third one on Shakira’s “Ojos Así”, the second one on Shakira’s “Suerte” and the first one on Shakira’s “La Tortura”. If you’ve got any suggestions as far as artists or songs go please put them in the comments, I’d love to hear them.

This is the 6th in a series of posts I’m doing where I help you learn Spanish from music videos and show you how I do it myself (that way you don’t have to wait for me to dissect a Spanish music video, you can go out and start doing it yourself with whatever songs you want and using it to teach yourself Spanish). I’ve done five other similar posts prior to this: the last one on Juanes’ ‘Yerbatero’, the fourth one on Shakira’s ‘Te Aviso, Te Anuncio’, the third one on Shakira’s “Ojos Así”, the second one on Shakira’s “Suerte” and the first one on Shakira’s “La Tortura”. If you’ve got any suggestions as far as artists or songs go please put them in the comments, I’d love to hear them.

About This Song

This song was originally released in English as part of Shakira’s She Wolf album (the Spanish version of which was called Loba) and was called Did It Again. The theme is a common one in Shakira songs: a male vs. female battle where the male is the bad guy, though in this case Shakira is at least admitting that this is a weakness of hers and really her own fault. The basic story line is that she has hooked up with this guy in a hotel room for a one-night stand, he’s married and hides the ring in his pocket, but she just can’t resist him and this is something she has this terrible habit of doing (she keeps “tripping on this same rock over and over”) so apparently this is one of many incidents like this, hence the title of the song in English, “Did It Again”.

Interestingly, according to Shakira, one of the main influences for this song were the paintings of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, a 19th Century Dutch painter, as well as something from Morocco known as “jidba”, which I’ve had a hell of a time looking up–as best I can ascertain, it’s a sort of trance-like state that a dancer will be in while performing during a Moroccan ceremony known as “Lila”:

lila – A night ritual of Gnawa people of Morocco. The Lila is a rich ceremony that follows a path through the night whose road is marked in the sensory realms of sound (music, song), sight (colors), smells (incense) and movement (dance). This musical ritual enables participants to enter a trance state of healing purification in which they may perform startling and spectacular dances. Lila in Sanskrit is the Cosmic Play.

Source: Hamsa Lila

Ground Rules

1. I will post the video below this. The way I want you to do this is to play it once all the way through, then let’s look at it and analyze it one verse at a time. Below the video will be the Spanish lyrics so that you can listen to the music video while following along with the lyrics–this is the intermediate step after you learn what the lyrics mean but before you can just listen to the song and understand everything without the lyrics to read. Having the actual Spanish being spoken in front of you in written form so you can follow along with the audio allows you to attune your listening comprehension, it’s that intermediate step that gets you to the point where you can understand everything being said without the lyrics to read, they’re sort of like training wheels (thanks to Eiteacher for this suggestion).

2. Under the lyrics will be my translation and analysis of what was said, here is where you’ll actually learn the Spanish that was spoken during the song. I will post the Spanish lyrics and then the English translation of them. Use the English lyrics and SpanishDict (I highly recommend you have this open in another tab while you’re doing this) to determine the definition of any words you don’t know (I will cover a lot of the words used, but not all of them)–if the regular definition of a particular word isn’t being used or the word is being used in such a way that simply knowing its definition won’t help you, I will explain it.

3. Next I will pick out various aspects of the Spanish that she’s using that I think require an explanation–I will not cover simple things like the definition of words like “el” (which means “the”), “ser” (which means “to be”), etc. unless there is something about the way they’re being used that I think warrants explanation. If you don’t understand what a word means, like I said, just check the English translation and/or SpanishDict. I will link to a lot of external sites with explanations for the grammar used, or the conjugation of a verb used, or the definition of a word–I’m doing this because I don’t have the space here to explain every single detail of what’s going on, there’s an enormous amount of Spanish being used in a single song like this which is precisely why I advocate this method (this is essentially The Telenovela Method, FYI), because you can learn so much from a single song or movie or book, etc. If you don’t understand a grammatical term that I use and it’s a link, click it!

4. Now, go back and play the verse we just analyzed several times and see if you can hear and understand everything being said, then go on to the next one.

5. If you are confused about anything and feel there’s something I didn’t cover or explain but should have, please let me know in the comments. As a matter of fact, please leave a comment and let me know what you think regardless, I need feedback and love getting it, each individual comment allows me to make an improvement or fix a problem thereby making this blog just a little bit better each and every time I get feedback of some sort. Oh, and you can also contact me via my contact form (this will go to my e-mail inbox).

The Video

The Lyrics

En la suite dieciséis

Lo que empieza no termina

Del mini bar al Edén

Y en muy mala compañíaEra ese sabor en tu piel

A azufre revuelto con miel

Así que me llené de coraje y me fui a caminar por el lado salvajePensé “no me mires así”

Ya sé lo que quieres de mi

Que no hay que ser vidente aquí

Para un mal como tú no hay cuerpo que aguanteLo hecho está hecho

Volví a tropezar

Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Y contigo nunca es suficienteCómo fue

Qué pasó

Esa noche

ImpacienteFueron a llamar

La de recepción

Cuando se quejaba

La de diecisieteNo puede ser nada normal

Acabar eligiendo tan mal

En materia de hombres soy toda una experta siempre en repetir mis errores

No hay ceguera peorQue no querer mirar

Cuando te guardabas el anillo dentro del bolsillo y dejarlo pasarLo hecho está hecho

Volví a tropezar

Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Y contigo nunca es suficienteNunca me sentí tan fuera de lugar

Nunca tanto se escapó de mi control

Pero todo en este mundo es temporal

Lo eres tú y lo soy yoNunca me sentí tan fuera de lugar

Nunca tanto se escapó de mi control

Pero todo en este mundo es temporal

En eso no decido yoLo hecho está hecho

Volví a tropezar

Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Y contigo nunca es suficienteSe siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Translation and Analysis

First Verse:

En la suite dieciséis

Lo que empieza no termina

Del mini bar al Edén

Y en muy mala compañía

Translation:

In suite sixteen

That which starts doesn’t end

From the mini-bar to Eden

And in very bad company

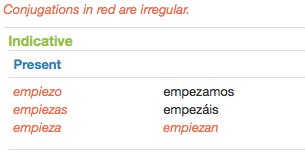

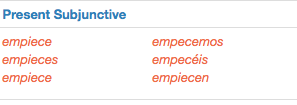

Alright first of all let’s look at what words we don’t know here, you can probably guess the obvious such as “suite” meaning “suite” as in a hotel suite, “lo” can mean “he/she” or “it” but in conjunction with “que” as in “lo que” you get a very common expression that best translates to “that which”. “Empezar” is an irregular verb in Spanish that means “to begin”, irregular means that the conjugation isn’t the standard -ar verb conjugation, the change comes at the end and you will see this same change with all such verbs ending in “-ezar”, the only thing different you do is add an “i” before the second “e” for all forms in the present and present subjunctive except nosotros and vosotros as well as change the “z” to a “c” in the present subjunctive, as such (credit: SpanishDict’s fantastic conjugation tool):

A piece of advice: don’t try to memorize this directly, instead memorize and learn how to use it at the same time by actually using it, I personally recommend a website called Lang-8 where you can write anything you want and have it reviewed and corrected by a native speaker for free. Take any new Spanish you’ve just learned and use it to write up a couple paragraphs or a sentence or two or whatever on there, actually use it, that’ll make you remember it better than nearly any memorization technique.

A piece of advice: don’t try to memorize this directly, instead memorize and learn how to use it at the same time by actually using it, I personally recommend a website called Lang-8 where you can write anything you want and have it reviewed and corrected by a native speaker for free. Take any new Spanish you’ve just learned and use it to write up a couple paragraphs or a sentence or two or whatever on there, actually use it, that’ll make you remember it better than nearly any memorization technique.

Alright, moving on, “terminar” simply means “to end” but you’ve already guessed that, so the line “lo que empieza no termina” means “that which begins doesn’t end”. In the line “Del mini bar al Edén” you get the two most common contractions in Spanish together in the same sentence, how lovely: “al” (which is “a” + “el”) and “del” (which is “de” + “el”), so “Del mini bar al Edén” means “From the mini bar to the Eden” (we would normally leave out the “the” in reference to a place name like “Eden”, Spanish does not). For what it’s worth I highly suspect she’s talking about sex, which apparently began at the mini-bar.

Next line: “Y en muy mala compañía”. Very simple, “Y” means “and”, “en” means “in”, and “compañia” means “company” in terms of the people around you and “mal” means “bad”, which in this case has been modified to “mala”, making it feminine in order to match the gender of the noun, “la compañia”.

Next verse:

Era ese sabor en tu piel

A azufre revuelto con miel

Así que me llené de coraje y me fui a caminar por el lado salvaje

Which means:

It was that taste of your skin

Like sulfur mixed with honey

So that I was filled with courage and went to walk on the wild side

Ok, first line: “Era ese sabor en tu piel”. Now “era” is the 3rd person singular imperfect form of “ser” (“to be”). “Ese” means “that”, in reference to “sabor” which is a masculine noun (but we knew that since it was “ese” instead of “esa”) that means “taste”.

Now we get to something really interesting that I haven’t seen before (and just had to ask the awesome folks over at the WordReference forums about): the use of “A” to mean “like” in the line “A azufre revuelto con miel” which translates to “Like sulfur mixed with honey”. “A” almost always means “at” or “to” or some very similar variation of those two (occasionally they’ll use it where we would use “in”), but occasionally it’s used to mean “like” and in particular you will very frequently see it paired up with the noun “sabor” as we do here, in fact if you go and look up the definition of “sabor” on SpanishDict (please click) you’ll note that the second example sentence they use for the primary definition of “sabor” (which is “taste”) is:

con sabor a limón = lemon-flavored

Another common use of “a” to mean “like” is with “parecer” (“to look like”), e.g. “Te pareces a tu papá – you look like your father.”

Moving on, “azufre” simply means “sulfur” and “miel” means “honey” (quick trivia, the United States is known, sometimes seriously and sometimes in jest, in Colombia as “the land of milk and honey” or “la tierra de leche y miel”, meaning that the U.S. is paradise and everything is wonderful there). Now, the verb “revolver“, which normally means “to turn around” can also mean “to mix or stir”, so the past participle could, of course, mean “mixed” or “stirred”, right? Right. And in this case it (“revuelto”) does, so we finally get “like sulfur mixed with honey” out of “A azufre revuelto con miel”. Savvy? 😉

Next line: “Así que me llené de coraje y me fui a caminar por el lado salvaje”. “Así” just means “this way” or “like this” or “so that” (which is how it’s used here, this is probably the most common way that “así” is used). Next we get to the verb “llenar” which means “to fill”, and in this case she’s being filled with courage, “coraje”, so that she can take a walk on the wild side: “me fui a caminar [to walk] por[on] el lado [side] salvaje [wild]”. “Fui” is just the preterite of “ir”: when “ir” is pronomial (aka “reflexive”) it means “to leave” or “to go” in reference to a person, so when she says “me fui” she’s saying “I went”. So, the full translation is:

“Así que me llené de coraje y me fui a caminar por el lado salvaje” = “So that I was filled with courage and went to walk on the wild side”

Got it?

Next verse:

Pensé “no me mires así”

Ya sé lo que quieres de mi

Que no hay que ser vidente aquí

Para un mal como tú no hay cuerpo que aguante

Which means:

I thought “don’t look at me like that”

I already know what you want from me

One doesn’t have to be a clairvoyant here

For an illness like you there isn’t a body that will tolerate it

Ok, first line: Pensé “no me mires así”. “Pensé” is just the preterit form of pensar (“to think”), and “no me mires así” is a command, therefore “mires” is the negative informal imperative form of “mirar” which means “to look at or watch”. Now, something funny is going on here if you’re really paying close attention: “mirar” is an -ar verb and therefore the informal (tu form) imperative should end in “a”, right? It should be “mira”, it should end in “a” and that “s” certainly shouldn’t be there right? Normally yes, but when an imperative in the familiar second person form (that is, either tú or vosotros) is negative things change: you actually switch the “e” to an “a” and add an “s” for -er/-ir verbs and the “a” to an “e” and add an “s” for -ar verbs (confusing, I know, I still slip up on this one). Ok, here are some examples to help you understand how this works:

¡Mira lo que ha hecho! = Look what you’ve done!

In this case “mirar” is put into the imperative tú form simply by taking the “r” off the end, it’s just like the regular present tú form except there’s no “s” on the end (“miras”). This is how it’s done for the affirmative imperative (affirmative simply means “not negative”, that is we’re not saying “don’t look”). The negative imperative in the familiar (tú) form is a bit different:

¡No mires allí! = Don’t look there!

In this case, it’s imperative, it’s in the tú form, and it’s negative: this means that it’s going to change, it’s not going to be “no mira allí”, we’re going to change the “a” to “e” and add an “s”, so we get “no mires allí”. Why do they do this? I have no idea and I doubt anyone else really knows either, a lot of grammar rules don’t really have much rhyme or reason to them, they just are the way they are because that’s how the language evolved over time and no one ever designed it a certain way for a certain reason.

Sorry, if you’re not familiar with this it’s horribly confusing, I came to fully understand this stuff only after running into it several times and relearning it each time. I highly recommend you read two additional articles that give this subject much more detailed treatment than I can here: Informal Commands on StudySpanish.com and Positive and Negative Commands in Spanish on About.com.

“Así”, as we’ve discussed already, means “this/that way” or “like this/that”.

Next line: Ya sé lo que quieres de mi. “Ya” means “already”, “sé” is just the present “yo” form of “saber“, which means “to know”, so “sé” means “I know”, “lo que” means “that which”, “quieres” is just the present “tú” form of “querer” which means “to want”, and “de mi” simply means “from me”, so we get the literal translation of “Already I know that which you want from me”, which is better translated as:

“Ya sé lo que quieres de mi” = “I already know what you want from me”

Easy. Next line: Que no hay que ser vidente aquí. “Que” just means “that” in the sense of “such that”, as in “I already know what you want from me [ya sé lo que quieres de me] such that you don’t have to be psychic to see it [que no hay que ser vidente aquí].”, got it? “Hay que” is just a common expression that means “one must do something”, in this case “one must not be a psychic” in the form of “no hay que ser vidante”. “Vidente” literally means “one who sees” but is simply a common term for “clarivoyant” or a “psychic”. So we get:

“Que no hay que ser vidente aquí” = “One doesn’t have to be a clairvoyant here”

Next line: Para un mal como tú no hay cuerpo que aguante. “Para” just means “for”, “un mal” could mean a few things here: “mal” as a noun as it’s used here could mean “evil”, “harm or damage”, “illness”, or simply “bad thing”. But considering the fact that it’s referring to something that a body cannot stand, I’m definitely going to go with “illness”, make sense? So by saying “para un mal como tú” she’s saying “for an illness like you”. Next, “no hay” just means “there isn’t” in a general sense: “hay” is a word you’re going to see a lot, it’s technically the 3rd person present conjugation of “haber”, which means “to have”, but “hay” almost never means “have”, it’s a general expression that means “there is” or “there are”–check out the definition of “haber” and scroll down to where it says “verb impersonal” and you’ll see it. So “no hay cuerpo” means “there isn’t a body”, ok? Now, the last bit, “que aguante”, is pretty simple: “aguantar” means “to bear, stand, or tolerate” and it’s in the subjunctive because it’s something that’s hypothetical and therefore not certain and so “aguante” sort of means something like “would be able to stand [if this were to happen]”–for more information about the subjunctive check out my post called The Spanish Subjunctive Explained. If you read that article, “aguante” in this case would fall under the “Doubt/Denial” section of W.E.I.R.D.O. Alright, so here’s what we got:

“Para un mal como tú no hay cuerpo que aguante” = “For an illness like you there isn’t a body that will tolerate it”

Next verse:

Lo hecho está hecho

Volví a tropezar

Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Y contigo nunca es suficiente

Which means:

What’s done is done

I tripped up again

On the same stone that’s always been there

Everything bad that happens, feels so good

and with you it’s never enough

Ok, first line: Lo hecho está hecho. Here, “lo” is being used to mean “that which”, as in “that which is done” (“hecho” is the past participle of “hacer”, which means “to do”, so “hecho” means “done”). If you’ll check out the definition of “lo” and look under “article (neutro)” you’ll see what I mean, “lo antigua” means “that which is antique”, “lo mejor” means “that which is the best”, etc. This is one of those words that can mean a million different things depending on how you use it and you just have to see it used a bunch of different times and get used to it before you will understand it. So “lo hecho está hecho” literally means something like “that which is done is done”, or a better translation would be: “what’s done is done”.

Next line: Volví a tropezar. Ah. This one’s screwy. Well, what’s screwy is the way that “volver” is used in this instance, and you’ll see this elsewhere as well: “volver + X” can frequently mean “I/you/they did X again” because “volver” means “to return” when referring to a person (look at the definition under “instransitive verb”) so they’re saying that they ‘returned’ to doing X, meaning that they did it again. Oh, and “tropezar” means “to trip or stumble”. So “volví a tropezar” literally translates to “I came back to tripping”, so what it really means is:

“Volví a tropezar” = “I tripped again”

Next line: Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre. Not much going on here, “Con la misma” means “with [con] the [la] same [misma]”, “piedra” means “stone” and “hubo” is just the preterit form of “haber”, which as we’ve discussed is most commonly used to mean “there is/are”, so if it’s in the preterit then that means that “hubo” means…what? “There was/were”, right? Yup! You got it. And “siempre” means “always”, so literally it means “With the same stone that was always”, or properly translated:

“Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre” = ” On the same stone that’s always been there”

Next line: Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal. Ok, here we’re seeing the use of something called the impersonal se: this is used to express a general statement, e.g. “one feels X” or “one does X” or “it feels X”, etc. It’s sort of like what we call “the royal ‘you'” in English, e.g. if someone says “If you break the law, you might go to jail.” they’re not necessarily talking to anyone in particular but in general, another less common way of saying precisely the same thing would be “If one breaks the law, one might go to jail”–it’s sort of a general non-specific statement, it’s not addressing anyone in particular. That’s how “se” is being used here, in this case “se siente” means “it feels”, not necessarily “I feel” or “I felt” or that anyone in particular “felt” something, but just that if one is in that particular situation then one “feels” a certain way. Here are a few examples in English and Spanish:

“Taking a shower feels good” = “Ducharse se siente bien”

“Chocolate tastes good” = “El chocolate se sabe bien.”

These are general statements and we make them by using “se” + 3rd person present form of the verb (the present ‘usted’ or ‘ustedes’ form).

Moving on: “Se siente tan bien…”: “tan” is a word that means “so”, essentially, in the sense that it emphasizes quantity, e.g. “so much” or “so many”, e.g. “I had so many chocolates I felt sick”, in this case “tan” + “bien” = “so good”, so we get: “se siente tan bien” = “it feels so good”, right? Right.

The rest is pretty straightforward: “todo lo que hace mal” = “everything [todo] that [lo] which [que] does [hace] bad [mal]”. Ok, we’ve covered the “lo que” thing before, “hace” is just the present singular form of hacer, nothing fancy there, and “mal” means bad. I think what I need to explain here is the overall meaning: she’s basically saying that everything that does bad stuff feels good, that is all things which do bad feel good, got it? The way we would say this in English is just slightly different but important to point out because otherwise this might confuse some people: we would say bad things feel good, the slight difference being that “bad” is describing the thing in English and in Spanish “mal” is describing the actions of those things. So in Spanish the actions are bad, in English the thing is bad–is there any difference in what’s being said? No, if the things something does are bad then it’s bad, if a thing is bad then it’s going to do bad things. I just wanted to point out this minor difference in semantics to prevent confusion (because it initially confused me, haha).

Last line, and it’s simple: Y contigo nunca es suficiente. “Contigo” is a contraction of “con” (which means “with”) and “ti” which means “you”, when it’s contracted the “go” is added to the end (probably to make it easier to pronounce, I don’t really know) and you get “contigo” which means “with you”. “Nunca” means “never”, “es” is the 3rd person present form of “ser“, and “suficiente” means “sufficient” or “enough”. Simple. So we get:

“Y contigo nunca es suficiente” = “and with you it’s never enough”

Next verse:

Cómo fue

Qué pasó

Esa noche

Impaciente

Which translates to:

How it was

What happened

That night

Impatient

Oh good, a short and easy one: do I really need to explain much here? I think we might be able to knock this whole verse out in one paragraph. “Fue” is just the preterite of “ser“, so “fue” means “was”, and of course “cómo” means “how”. “Qué” means “what” and “pasó” is just the preterite of “pasar” which primarily means “to pass” but that can be “to pass” in the sense of “to occur” or “to happen” (check the definition, scroll down, it’s there), “Qué pasó” means “what happened”. In fact, a very common greeting is “¿Qué pasa?” which means “what’s happening?”, and the way you would ask somebody “What happened?” would be…guess…”¿Qué pasó?”. “Esa” means “that”, “noche” means “night”, and “impaciente” means “impatient”. That’s it.

Next verse:

Fueron a llamar

La de recepción

Cuando se quejaba

La de diecisiete

Which translates to:

They went to call

The girl from reception

When she was complaining

The girl in room 17

“Fueron” is just the 3rd person plural preterite of “ir“, so it means “they went”, and “llamar” means “to call”, so we get “Fueron a llamar” = “They went to call”.

“La de recepción” means “The girl from reception”, in other words the receptionist, who is apparently female. Now how does “la” mean “the girl”? Simple, “la” is a direct object pronoun and like other direct object pronouns (such as “lo”) it can mean a person or a thing, in this case since it’s feminine (the masculine equivalent is “lo”), it must be referring to either a female person or a thing which is feminine (that is, the word for that thing is feminine, e.g. “la casa”), and in this case we can determine from the context that it’s a person because whatever it/she is, it/she is at the reception desk and they’re going to call it/her, so that kind of narrows it down, doesn’t it? And of course “de” means “from” and “recepción” means “reception”, so “la de recepción” means literally “her from reception”, which better translates to “the girl from reception”.

Cuando se quejaba. “Cuando” means “when”, simple, and then it gets a bit more complicated…ok, first of all we run into “se” again, but in this case it’s not being used the way it was before as the impersonal “se”, it’s reflexive, which means that “se” represents a specific person, the one doing the action (complaining, in this case, as that what “quejar” means), and it shows that they’re doing the action to themselves. Complaining to themselves? Errmm, yes, no, not literally. Remember I said grammar didn’t have to make sense, that it was kind of arbitrarily determined and a lot of it doesn’t have a good reason for being done the way it is? Right. Well, a lot of verbs in Spanish are almost always reflexive, especially when a person is doing them, simply because they are. “Quejarse“, which means “to complain”, is one of them (notice how the word is “quejarse”, not “quejar”, there isn’t even a “quejar” listed in the dictionary: go ahead and try to look it up, see what happens). The way I would say “I’m complaining” would be “Me quejo”, the way I would say “I’m going to complain” would be “Voy a quejarme”, see how it’s reflexive each time no matter what?

“But that doesn’t make sense.” No, it doesn’t, but that’s still the way you do it. Haha, isn’t this fun? 😀

“But is there some way of determining whether a verb should be reflexive, like a pattern or rule like ‘i before e except after c’ or something?” No.

“So I just have to memorize them individually and remember whether or not each verb is reflexive before I use it?” Yes.

“Well that sucks.” Yes, it does.

Moving on…La de diecisiete. Same thing as above with “la”, it represents a girl. Apparently it was a girl in room 17, the one right next to theirs (remember at the beginning of the song, the very first line, where they told you they were in room 16?) who called down to reception to complain (I think Shakira’s implying that maybe she was jealous of all the fun Shakira and her lover were having next door…or maybe the noise was just keeping her up).

How did I determine this? Context: “When they complained, la de diecisiete” so whatever or whoever was complaining is expressed here by “la”, and things don’t complain, people do, so it was a person that complained and they were female because it’s “la” instead of “lo”. This, by the way, is also why the preceding line, “Cuando se quejaba”, was translated as “When she complained” instead of “When they complained” 😉

Oh, and diecisiete, of course, means seventeen.

Next verse:

No puede ser nada normal

Acabar eligiendo tan mal

En materia de hombres soy toda una experta siempre en repetir mis errores

No hay ceguera peor

Which means:

It can’t be anything normal

To end up choosing so badly

In the matter of men I am always a complete expert in repeating my mistakes

There isn’t a worse blindness

No puede ser nada normal is easy, “puede” is the present form of “poder” which means “to be able to”, “ser” means “to be”, “nada” means nothing, and “normal” means “normal”. Done. Next.

Acabar eligiendo tan mal. “Acabar” means “to end or finish”, “eligiendo” is just the gerund of “elegir” which means “to choose”, we’ve already covered “tan”, and “mal” means “bad”. The way “acabar” is being used threw me for just a second initially, but it became apparent that this is simply how they say “to end up”, they just use the infinitive of “acabar”, so she’s literally saying “to end choosing so badly” or “to finish choosing so badly”, but what she means is “to end up choosing so badly”.

En materia de hombres soy toda una experta siempre en repetir mis errores. Agh, long sentence! But not particularly complicated or tricky. “Materia” simply means “matter”, as in “the matter at hand”, “hombre” means “man” so “en materia de hombres” means “in the matter of men”. “Soy” is the first person present form of “ser“, so “soy” means “I am”, “toda” in this case means “completely” (check the definition, scroll down, it’s one of the secondary definitions and the one that makes the most sense here: context, context, context), “experta” means, you guessed it, “expert”, and “siempre” means “always”–so now we’ve got “soy toda una experta siempre”, which means “I am completely an expert always” or, a little bit better translation could be done by switching the word order to make it a bit more English-friendly by saying: “I’m always a complete expert”. Lastly, we have “en repetir mis errores”: “repetir” means “to repeat”, “mis” is the plural “my”, and “error” means…yeah, “error”. Told you it wasn’t complicated. Let’s put it all together:

“En materia de hombres soy toda una experta siempre en repetir mis errores” = “In the matter of men I am always a complete expert in repeating my mistakes”

Last line: No hay ceguera peor. Again, we run into “hay“: I told you this was common. So “no hay” means…right, “there isn’t” or “there aren’t”, depending on the context, and in this case it’s “there isn’t” because the object, “ceguera” is singular, not plural. “Ceguera” means blindness, and “peor” means worse, so we literally get “there isn’t blindness worse”, or better translated: “There is no worse blindness”.

Next verse:

Que no querer mirar

Cuando te guardabas el anillo dentro del bolsillo y dejarlo pasar

Which means:

To not want to look

When you kept the ring inside your pocket and letting it happen

Que no querer mirar. This is a bit confusing, I know, “que” would just mean “that” as it normally would, but we have the infinitive of “querer” (which means “to want”), so in this case “que” coupled with an infinitive like that means something more like “to not [infinitive]”, in this case “to not want”. “Mirar” means “to look”, so she’s saying “to not want to look” in reference to herself, that is she didn’t want to look. Ok, I’ll give an example in English: let’s say I’m talking about the one time I passed up the opportunity to eat cheese, and hypothetically let’s say I love cheese and would never do that, but I did it once, so I shake my head and say “To pass up the opportunity to eat cheese like that…I just…I don’t know what was wrong with me”–see how I used “to pass up” like that? I didn’t say “I passed up”, I said to pass up, I used the infinitive in English by adding “to” to the verb “pass”, but I was still talking about myself. So when she says “to not want to look” she’s talking about how she didn’t want to look, got it?

I’ll give some examples in Spanish:

“Que simplemente salir cómo eso…no es bien.” = “To simply leave like that…it isn’t right.”

“Que no ayudar a ella…creo que eso estaba mal.” = “To not help her…I think that was wrong.”

Next line: Cuando te guardabas el anillo dentro del bolsillo y dejarlo pasar. “Cuando” means “when”, “guardar” means “to keep” and it’s in the imperfect informal form here because she’s speaking to her lover, so of course she uses “tú” with him because their relationship is familiar and informal. “Anillo” means “ring”, “dentro” means “inside” or “in”, “bolsillo” means “pocket”, “dejar” means “to let”, and “pasar“, as we’ve already noted, means “to happen”. The “lo” attached to the end of “dejar” simply means “it” in reference to his action of putting the ring in his pocket, so “dejarlo pasar” means “to let it happen” or “letting it happen”. So, putting it together we literally get something like: “When you were keeping the ring inside of the pocket and to let it happen” which might sound strange, especially with the bit at the end, but it has to be take in context with the previous line (the two lines together are really one whole sentence, not two separate ones):

“Que no querer mirar cuando te guardabas el anillo dentro del bolsillo y dejarlo pasar” = “To not want to see when you were keeping the ring inside of the pocket and to let it happen.” This is still a literal translation but does it make a bit more sense? Let’s translate it properly into English:

“Que no querer mirar cuando te guardabas el anillo dentro del bolsillo y dejarlo pasar” = “To not want to look

when you kept the ring inside your pocket and to let it happen”

And, of course, she’s talking about herself here, she’s criticizing herself for ignoring the fact that he’s married and has a ring in his pocket and then letting it happen.

Next verse:

Lo hecho está hecho

Volví a tropezar

Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Y contigo nunca es suficiente

This is just the chorus repeating a verse we’ve already covered. Next.

Nunca me sentí tan fuera de lugar

Nunca tanto se escapó de mi control

Pero todo en este mundo es temporal

Lo eres tú y lo soy yo

Which means:

I’ve never felt so out of place

Never has so much escaped my control

But everything in this world is temporary

You are and so am I

Nunca me sentí tan fuera de lugar. “Nunca” means “never”, and “me sentí” is the first person preterit of “sentir“, which means “to feel”, which is another one of those almost-always-reflextive verbs, and when you’re using it to describe how a person feels or felt you will always make it reflexive as we see here. “Tan” we’ve already covered, that means “so” as in “very”, so “tan fuera de lugar” means “so out of place”. “Fuera” normally means “outside” or “away” and coupled with “lugar“, which means “place”, we get the phrase “fuera de lugar” which literally and contextually translates to “out of place”. So we get:

“Nunca me sentí tan fuera de lugar” = “I’ve never felt so out of place”

Next: Nunca tanto se escapó de mi control. “Tanto” is very similar to “tan” and just means “so much”, “escapó” is the singular 3rd person preterit of “escapar” means “to escape” and it’s reflexive because the things that escaped her did the escaping, not her, she’s not saying she escaped, she’s saying that things escaped themselves from her (note my use of the word “themselves” there, that indicates that it’s reflexive: verbs that are reflexive do the action they do to the subject, right? right). The subject that escaped is “the things”, so the subject is doing the action (escaping) to itself, hence the use of the reflexive. A great way to explain this is to look at precisely how we might say this in English: “Things escaped me.”: now, who’s doing the escaping, who’s the subject? The things are, you are the object.

Anyway, the rest is pretty self-explanatory: de mi control. “Control” means…”control”, right. So “de mi control” means “from my control”. Let’s put it all together:

“Nunca tanto se escapó de mi control” = “Never has so much escaped my control”

Next line: Pero todo en este mundo es temporal. Easy. Most of this we’ve already covered, “todo” means “everything”, “este” means “this”, “mundo” means “world”, and “termporal” means “temporary”. Done. What does it mean?

“Pero todo en este mundo es temporal” = ” But everything in this world is temporary”

Next: Lo eres tú y lo soy yo. “Lo” means “it” in reference to “temporary” in the previous line, so she’s saying that both him and her are temporary (“hey, we’re gonna die some day so let’s get it on!”). “Eres” is the present familiar form of “ser“, and “soy” is the present 1st person form of “ser”, so “eres” means “you are”, and “soy” means I am. Literally the sentence, “lo eres tú y lo soy yo” means something like “it you are and it am I”, or correctly translated:

“Lo eres tú y lo soy yo” = “You are and so am I”

Next verse:

Nunca me sentí tan fuera de lugar

Nunca tanto se escapó de mi control

Pero todo en este mundo es temporal

En eso no decido yo

This is just the same verse repeated again except with a different line at the end: En eso no decido yo. “Eso” means “that” in reference to the previous line where she said they’re both temporary, “decido” is the present 1st person form of “decidir” so “decido” means “I decide”, so literally the line En eso no decido yo means something like “In that no decide I”, or more correctly:

“En eso no decido yo ” = “In that I do not decide”

Got it?

Next verse:

Lo hecho está hecho

Volví a tropezar

Con la misma piedra que hubo siempre

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

Y contigo nunca es suficiente

That’s just the chorus repeating a verse. Next.

Se siente tan bien todo lo que hace mal

And we’ve already covered that. We’re done!

Mother of god that was a long post. Major kudos to you if you made it through all of this in one sitting, because I sure as hell didn’t write it all in one sitting, I assure you that. Please, leave a comment and tell me what you think: any and all corrections and suggestions are more than welcome! Also… If you thought the above was at all useful and you want to learn (or are learning) Spanish, please give me a chance and read what I have to say about my book below! Thank you so much for checking out my blog and I hope you’ve enjoyed my writing.

I learned to speak conversational Spanish in six months using TV shows, movies, and even comics: I then wrote a book on how you can, too

I have a whole method and a book I wrote about it called The Telenovela Method where I teach you how to learn Spanish from popular media like TV shows, movies, music, books, etc. that you can all find online for free. It was the #1 new release in the Spanish Language Instruction section on Amazon for nearly a month after it came out and currently has 17 reviews there with a 4.9/5 stars average. It’s available for $7.99-$9.99 for the e-book version depending on who you buy it from (Kindle version on Amazon is now $7.99) and $16.99 for the paperback (occasionally a bit cheaper, again, depending on who you buy it from).

It’s currently available in both e-book and paperback from:

Cheers,

Andrew